Welina mai!

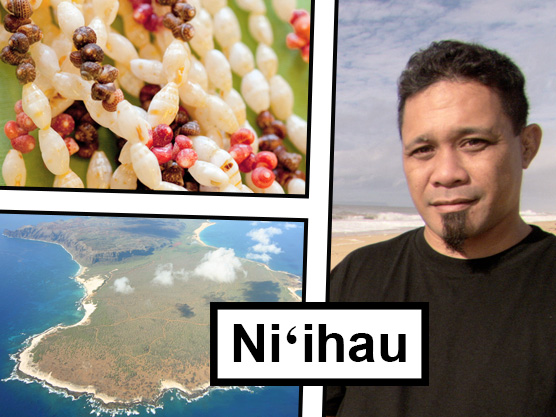

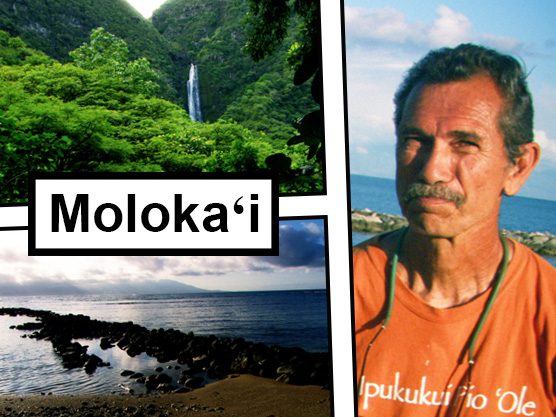

Welcome to Kumukahi, a website featuring a bilingual, community-based approach to presenting living Hawaiian culture and its connections to a rich ancestral past. Explore more than 60 diverse topics—from ahupua‘a to ‘ai pono, loina to lāhui, mo‘olelo to mo‘okū‘auhau—explained by cultural practitioners and community experts from across the pae ‘āina who have deep association with place and subject matter. Engaging videos, text pieces, and other educational activities and resources await you—your journey begins here at Kumukahi.